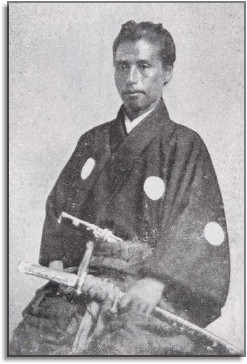

Photo from Takaaki Ishiguro

Ryoma : Life of a

Renaissance Samurai

by Romulus Hillsborough

First Literary Biography of Japan's Most Magnificent Samurai

|

Samurai Sketches

by Romulus Hillsborough

A collection of historical sketches from the bloody final years of

the Shogun, never before depicted in English

|

Katsu Kaishu, consummate samurai, streetwise denizen of

Downtown Edo, founder of the Japanese navy, statesman par excellence and always the

outsider, historian and prolific writer, faithful retainer of the Tokugawa Shogun and

mentor of men who would overthrow him was among the most remarkable of the numerous

heroes of the Meiji Restoration.

Kaishu's protégé was Sakamoto Ryoma, a key player in the overthrow of the Tokugawa

Shogunate. Surely Ryoma would agree that he owes his historical greatness to Kaishu, whom

Ryoma considered the greatest man in Japan.

Ryoma was an outlaw and

leader of a band of young rebels. Kaishu was the commissioner of the shogun¹s navy, who

took the young rebels under his wing at his private naval academy in Kobe, teaching them

the naval sciences and maritime skills required to build a modern navy.

Kaishu also imparted to

Ryoma his extensive knowledge of the Western world, including American democracy, the Bill

of Rights, and the workings of the joint stock corporation.

Kaishu was one of the

most enlightened men of his time, not only in Japan but in the world. The American

educator E. Warren Clark, a great admirer of Kaishu who knew him personally, called Kaishu

the Bismark of Japan, for his role in unifying the Japanese nation in the dangerous

aftermath of the fall of the Tokugawa.

Like Ryoma, Kaishu was an

adept swordsman who never drew his blade on an adversary, despite numerous attempts on his

life. Indeed the two men lived in dangerous times. I have been shot at by an enemy about

twenty times in all, Kaishu once said. I have one scar on my leg, one on my head, and two

on my side.

Kaishus defiance of death

sprung from his reverence for life. I despise killing, and have never killed a man. I used

to keep my sword tied so tightly to the scabbard, that I couldn't draw the blade even if I

wanted to.

Katsu Kaishu, who would

become the most powerful man in the Tokugawa Shogunate, was born in Edo in January 1823,

the only son of an impoverished petty samurai.

The Tokugawa had ruled

Japan peacefully for over two centuries. To ensure their supremacy over some 260 feudal

domains, the Tokugawa had strictly enforced a policy of national isolation since 1635. But

the end of the halcyon era was fast approaching, as the social, political and economic

structures of the outside world were undergoing major changes.

The nineteenth century

heralded the age of European and North American capitalism, and with it rapid developments

in science, industry and technology. The development of the steamship in the early part of

the century served the expansionist purposes of the Western powers. Colonization of Asian

countries by European powers surged. In 1818 Great Britain subjugated much of India.

Through the Treaty of Nanking, which ended the first Opium War in 1842, the British

acquired Hong Kong.

The Western encroachment

reached Japan in 1853, when Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy led a

squadron of heavily armed warships into the bay off the shogun¹s capital, forcing an end

to Japanese isolation and inciting fifteen years of bloody turmoil across the island

nation.

Until Perry's arrival,

pursuers of foreign knowledge existed outside the mainstream of Japanese society. Kaishu

was an outsider, both by nature and circumstance. But when his sword master urged him to

discontinue fencing to devote himself to the study of Dutch, with the objective to learn

Western military science, the young outsider balked.

That it was frowned upon

for a direct retainer of the shogun to study Dutch had little, if any, impact on Kaishu.

He was innately inquisitive of things strange to him. He was also filled with a burgeoning

self-confidence. But the idea of learning a foreign language seemed to him preposterous.

He had never been exposed to foreign culture, except Chinese literature. It wasn't until

age eighteen that he first saw a map of the world.

I was wonderstruck, he

recalled decades later, adding that he had now determined to travel the globe.

Kaishu's wonderment was

perfectly natural. His entire world still consisted of a small, isolated island nation.

But his determination to travel abroad was strengthened by his discovery of strange script

engraved on the barrel of a cannon in the compounds of Edo Castle.

The cannon had been

presented to Edo by the Netherlands, and Kaishu correctly surmised that the engraving was

in Dutch. Thus far he had only heard about those foreigners, the Dutch, who lived

in a small, confined community in the distant Nagasaki.

Those foreigners had

occasionally fluttered through his mind as mere phantasm, the stuff of youthful

imagination. But now, for the first time, he saw in his mind's eye, however vaguely, the

people who had manufactured the cannon, and who had engraved in their own language the

inscription upon its barrel.

Those undecipherable

letters of the alphabet, written horizontally rather than vertically, served as cold

evidence of the actual existence of people who communicated in a language completely

different from his own, but who until now had only existed as so much hearsay.

Since these foreigners

were human beings like himself, why shouldn¹t he be able to learn their language? And

once he had learned their language, he would be able to read their books, learn how to

manufacture and operate their cannon and realize his aspiration to travel the world.

In the face of Perry's

demands, the shogunate conducted a national survey, calling for solutions to the foreign

threat. The shogunate received hundreds of responses, the majority of which, broadly

speaking, represented either of two conflicting viewpoints.

On one side were those

who proposed opening the country to foreigners. Their opponents advocated preserving the

centuries-old policy of exclusionism. But neither side offered a constructive means for

realizing their proposals.

In contrast, the memorial

submitted by one unknown samurai was clear, brilliant, progressive, and included concrete

advice for the future of Japan. In his memorial Kaishu pointed out that Perry had been

able to enter Edo Bay unimpeded only because Japan did not have a navy to defend itself.

He urged the shogunate to recruit men for a navy. He dared to propose that the military

government break age-old tradition and go beyond birthright to recruit men of ability,

rather than the sons of the social elite, and certainly there was nobody in all of Edo

more poignantly aware of this necessity than this impoverished, brilliant young man from

the lower echelons of samurai society.

Kaishu advised that the

shogunate lift its ban on the construction of warships needed for national defense; that

it manufacture Western-style cannon and rifles; that it reform the military according to

modern Western standards, and establish military academies.

Pointing out the great

technological advances being achieved in Europe and the Untied States, Kaishu challenged

the narrow-minded traditionalists who opposed the adoption of Western military technology

and systems.

Within the first few

years after the arrival of Perry, all of Kaishu's proposals were adopted by the shogunate.

In January 1855, Kaishu was recruited into government service. In Japanese chronology this

corresponded to the second year of the Era of Stable Government, to which purpose Kaishu

dedicated the remaining forty-four years of his life.

In September, Kaishu

sailed to Nagasaki, as one of a select group of thirty-seven Tokugawa retainers to study

at the new Nagasaki Naval Academy, where he remained for two and a half years.

In January 1860 Katsu

Kaishu commanded the famed Kanrin Maru, a tiny triple-masted schooner, on the first

authorized overseas voyage in the history of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

Captain Katsu and Company

were bound for San Francisco. They preceded the Japanese delegation dispatched to

Washington aboard the U.S. steam frigate Powhatan to ratify Japan's first

commercial treaty.

After the arrival of the Powhatan,

they would return to Japan to report the safe arrival of the delegation. But more

significantly for Captain Katsu and Company was the opportunity to demonstrate the

maritime skills they had acquired under their Dutch instructors at Nagasaki, for, as

Kaishu emphasized, the glory of the Japanese Navy.

Kaishu remained in San

Francisco for nearly two months, observing American society, culture and technology. He

contrasted American society to that of feudal Japan, where a person was born into one of

four castes warrior, peasant, artisan, merchant and, for the most part, remained in

that caste for life.

Of particular interest to

Kaishu, who was determined to modernize and indeed democratize his own nation, were

certain aspects of American democracy.

There is no distinction

between soldier, peasant, artisan or merchant. Any man can be engaged in commerce, he

observed. Even a high-ranking officer is free to set up business once he resigns or

retires.

Generally, the samurai,

who received a stipend from their feudal lord, looked down upon the men of the merchant

class, and considered business for monetary profit a base occupation. Usually people

walking through town do not wear swords, regardless of whether they are soldiers,

merchants or government officials, while in Japan it was a samurai's strict obligation to

be armed at all times.

Kaishu also observed the

peculiar relationship between men and women in American society. A man accompanied by his

wife will always hold her hand as he walks.

The immense cultural and

social gaps notwithstanding, Kaishu, the outsider among his countrymen, was pleased with

the Americans.

I had not expected the

Americans to express such delight at our arrival to San Francisco, nor for all the people

of the city, from the government officials on down, to make such great efforts to treat us

so well.

In 1862, Kaishu was

appointed vice-commissioner of the Tokugawa Navy. He established his naval academy in Kobe

in 1863, with the help of his right-hand man, Sakamoto Ryoma.

The following year Kaishu

was promoted to the post of navy commissioner, and received the honorary title Awa-no-Kami,

Protector of the Province of Awa.

In October 1864, Kaishu,

who had thus far enjoyed the ear of the shogun, was recalled to Edo, dismissed from his

post and placed under house arrest for harboring known enemies of the Tokugawa. His naval

academy was closed down, and his generous stipend reduced to a bare minimum.

In 1866 the shogun's

forces suffered a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of the revolutionary Choshu

Army. Kaishu was subsequently reinstated to his former post by Tokugawa Yoshinobu, Head of

the House of Tokugawa, who in the following December would become the fifteenth and last

Tokugawa Shogun.

Lord Yoshinobu did not

like Kaishu, just as Kaishu did not like Lord Yoshinobu. Kaishu was a maverick within the

government, who had broken age-old tradition and even law by imparting his expertise to

enemies of the shogunate; who openly criticized his less talented colleagues at Edo for

their inability, if not blind refusal, to realize that the years, and perhaps even days,

of Tokugawa rule were numbered; who in the Grand Hall at Edo Castle had braved punishment

and even death by advising then-Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi to abdicate; and who was now

recalled to service because Yoshinobu and his aides knew that Kaishu was the only man in

all of Edo who wielded both the respect and trust of the revolutionaries.

In August 1866, Navy

Commissioner Katsu Kaishu was dispatched to Miyajima Island of the Shrine in the

domain of Hiroshima to meet representatives of Choshu.

Before departing he told

Lord Yoshinobu, I'll have things settled with the Choshu men within one month. If I'm not

back by then, you can assume that they've cut off my head.

Kaishu was aware of the

grave danger to his life as an emissary of the Tokugawa, but nevertheless traveled alone,

without a single bodyguard.

Shortly after

successfully negotiating a peace with Choshu, the outsider resigned his post, due to

irreconcilable differences with the powers that were, and returned to his home in Edo.

In October 1867, Shogun

Tokugawa Yoshinobu announced his abdication and the restoration of power to the emperor.

But diehard oppositionists within the Tokugawa camp were determined to fight the forces of

the new imperial government.

The leaders of the new

imperial government were equally determined to annihilate the remnants of the Tokugawa, to

ensure that it would never rise again.

Civil war broke out near

Kyoto in January 1868. Although the imperial forces, led by Saigo Kichinosuke of Satsuma,

were greatly outnumbered, they routed the army of the former shogun in just three days.

The new government's

leaders now demanded that Yoshinobu commit ritual suicide, and set March 15 as the date

fifty thousand imperial troops would lay siege to Edo Castle, and, in so doing, subject

the entire city to the flames of war.

The services of Katsu

Kaishu were once again indispensable to the Tokugawa. Kaishu desperately wanted to avoid a

civil war, which he feared would incite foreign agression. But he was nevertheless bound

by his duty as a direct retainer of the Tokugawa to serve in the best interest of his

liege lord, Tokugawa Yoshinobu.

In March 1868, with a

formidable fleet of twelve warships at his disposal, this son of a petty samurai was the

most powerful man in Edo. And as head of the Tokugawa army, he was determined to burn Edo

Castle rather than relinquish it in battle, and to wage a bloody civil war against Saigo's

forces.

When Kaishu was informed

of the imperial government's plans for imminent attack, he immediately sent a letter to

Saigo. In this letter Kaishu wrote that the retainers of the Tokugawa were an inseparable

part of the new Japanese nation. Instead of fighting with one another, those of the new

government and the old must cooperate in order to deal with the very real threat of the

foreign powers, whose legations in Japan anxiously watched the great revolution which had

consumed the Japanese nation for these past fifteen years.

Saigo replied with a set

of conditions, including the peaceful surrender of Edo Castle, which must be met if the

House of Tokugawa was to be allowed to survive, Yoshinobu's life spared, and war avoided.

At an historic meeting

with Saigo on March 14, one day before the planned attack, Kaishu accepted Saigo's

conditions, and went down in history as the man who not only saved the lives and property

of Edo's one million inhabitants, but also the entire Japanese nation.

Copyright(c)2002 Romulus Hillsborough

To be continued with Sakamoto Ryoma

(Romulus Hillsborough is the

author of RYOMA - Life of a Renaissance Samurai (Ridgeback Press, 1999) and Samurai

Sketches: From the Bloody Final Years of the Shogun (Ridgeback Press, 2001) RYOMA is the

only biographical novel of Sakamoto Ryoma in the English language. Samurai Sketches is a

collection of historical sketches, never before presented in English, depicting men and

events during the revolutionary years of mid-19th century Japan. Reviews and more

information about these books are available at www.ridgebackpress.com.)

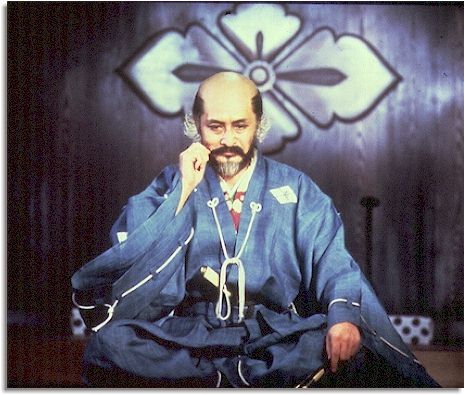

The Shadow Warrior - Kagemusha

1980, Spherical Panavision, color, 179

min [US version 162 min]

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Cast:Tatsuya Nakadai (Shingen Takeda and his double, the Kagemusha), Tsutomu

Yamazaki (Nobukado Takeda, Shingen's brother), Kenichi Hagiwara (Katsuyori Suwa [Takeda],

Shingen's son), Kota Yui (Takemaru Takeda, Shingen's grandson), Shuji Otaki (Masakage

Yamagata, Takeda Clan general, Fire Battalion leader), Hideo Murata (Nobuharu Baba),

Takayuki Shiho (Masatoyo Naito), Shuhei Sugimori (Masanobu Kosaka), Noboru Shimizu

(Masatane Hara), Koji Shinizu (Katsusuke Atobe), Sen [Ren?] Yamamoto (Nobushige Oyamada),

Daisuke Ryu (Nobunaga Oda, Shingen's enemy), Masayuki Yui (Ieyasu Tokugawa, Shingen's

enemy), Yasuhito Yamanaka (Ranmaru Mori), Takashi Shimura (Gyobu Taguchi), Jinpachi Nezu

(Sohachiro Tsuchiya, Shingen's bodyguard), Mitsuko Baisho (Oyunokata, Shingen's

concubine), Kaori Momoi (Otsuyanokata, Shingen's concubine), Akihiko Sugizaki (Noda Castle

solider), Toshiaki Tanabe (Kugutsushi), Yoshimitsu Tamaguchi (salt vendor), Takashi Ebata

(monk), Kumeko Otowa (Takemaru's nurse), Kamatari Fujiwara (doctor), Senkichi Omura

(Takeda's stable boy), Tetsuo Yamashita, Kai Ato, Yutaka Shimaka, Eiichi Kanakubo, Yugo

Miyazaki, Norio Matsu, Yasushi Doshita, Eihachi Ito, Noboru Sone, Masatsugu Kuriyama,

Takashi Watanabe.

Comments:

During Japan's 16th-century warring states period, a condemned thief is saved from

execution by agreeing to serve as a double for Takeda Shingen. Shingen is a powerful

military leader, but when he dies the thief (in his role as "shadow warrior") is

now doomed to play him forever. He even begins to think of himself as Shingen. Only

Shingen's horse can tell the difference, and that is the shadow warrior's undoing.

Notes:

Produced by Francis Ford Coppola and

George Lucas; Assistant Producer, Audie Bock (they got Fox and Toho to put money up

jointly). At $6 million dollars it was the most expensive Japanese film to date and the

first distributed by and invested in by a foreign company. It became an international hit.

While three of Japan's four big studios lost money in 1980, because of Kagemusha

Toho's profits increased by more than 50 percent

Kurosawa made the film partly as a dress

rehearsal for Ran.

Shimura's role cut from the US release

(162 min).

Ten years since Kurosawa had made a film

in Japan.

The lead actor was originally Shintaro

Katsu (famous for his role in the Zato Ichi series) but he was fired about 10 days in to

the shoot. Katsu purportedly had begun to doubt Kurosawa's ability as a director (thinking

him too old), and hired his own independent cameraman to video tape scenes which he would

view as private rushes before continuing. The set was marked by constant bickering.

Kurosawa fired Katsu, reportedly, after punches were thrown.

Kinema Junpo award in 1980 for Best

Supporting Actor (Tsutomu Yamazaki), nominated for an Academy Award for best

Foreign-Language Film (lost to Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears), co-winner of the

Grand Prize at Cannes.

Japanese

Rifles of World War II

by Duncan O. Mc Collum Paperback (January

1996)

Excalibur Publications

Japanese

Hand Guns

by Leith Hardcover (July 1976)

Borden Pub Co

Military

Pistols of Japan

Military

Pistols of Japan

by Fred L., Jr. Honeycutt Hardcover 3rd edition (November 1991)

Julin Books

Military

Rifles of Japan

by Fred L., Jr. Honeycutt F. Patt Anthony Hardcover

5th

Japanese Army

Handbook 1939-1945

by George Forty

Hardcover -

288 pages 1 edition (July 1, 1999) Sutton Pub Ltd

Japanese Rifles of

World War II

by Duncan O. McCollum

Paperback (January 1996)

Excalibur Publications |